The Whitlam government gave us no-fault divorce, women’s refuges and childcare. Australia needs another feminist revolution

Australia’s history of women and political rights is, to put it mildly, chequered. It enfranchised (white) women very early, in 1902. And it was the first country to give them the vote combined with the right to stand for parliament.

But it took 41 years for women to enter federal parliament. The first two women federal MPs, Dorothy Tangney and Enid Lyons, were just memorialised with a joint statue in the parliamentary triangle. It was unveiled this month – finally redressing the glaring absence of women in our statues.

Australia’s record of women’s rights is still uneven. We pioneered aspects of women’s welfare, such as the 1912 maternity allowancethat included unmarried mothers. But now, Australian women’s economic status is shameful.

As Minister for the Environment Tanya Plibersek notes in her foreword, Australia has plunged from the modest high point of 15th on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap index to 43rd in 2022.

What Whitlam did for women

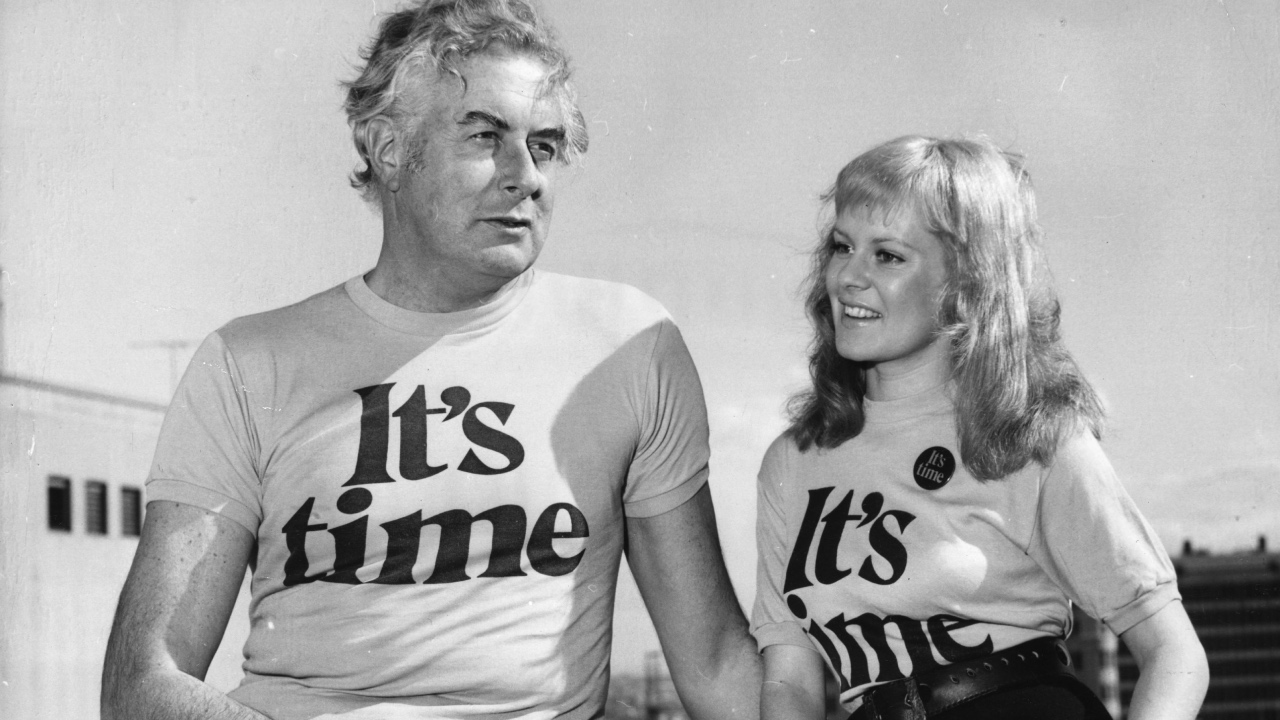

Federation was an exciting time for women. But the next peak didn’t arrive until the 1970s, when the Whitlam Government proved a beachhead for women’s rights. Feminism helped to swell the tide of change carrying Gough Whitlam to power in 1972.

But just how did Whitlam conceive his agenda for women? What were his short-lived government’s many achievements in this area? Until now, these questions haven’t been fully studied.

Women and Whitlam is important not just for taking on this task, but for its stellar cast of essayists. Many of them were feminist activists in the 1970s, and their memories add rich narrative detail.

The book is edited by Michelle Arrow, a Whitlam InstituteResearch Fellow and an authority on women, gender and sexuality in the 1970s: not least through her prize-winning monograph, The Seventies.

This excellent collection’s origins lie in a conference held at Old Parliament House in November 2019, organised by the Whitlam Institute. The book has been several years in the making, but its timing is perfect. Its month of publication, April 2023, is the 50th anniversary of Gough Whitlam’s appointment of Elizabeth Reid as his adviser on women’s affairs. This role, as an adviser to a head of government, was a world first.

In her introduction, Arrow points out Whitlam’s 1972 election speech only outlined three “women’s issues” as part of his program. But she also notes the late (former Senator) Susan Ryan’s excited response when she heard him begin it with the inclusive words, “Men and women of Australia” – a symbolic break from tradition. Iola Mathews, journalist and Women’s Electoral Lobby activist, captures the speed with which Whitlam acted on women’s issues, "In his first week of office he reopened the federal Equal Pay case, removed the tax on contraceptives and announced funding for birth control programs."

Arrow summarises what else the Whitlam government did for women. It extended the minimum wage for women and funded women’s refuges, women’s health centres and community childcare. It introduced no-fault divorce and the Family Court. It introduced paid maternity leave in the public service. And it addressed discrimination against girls in schools. Women also benefited from other reforms, like making tertiary education affordable.

A world-first role

Elizabeth Reid’s chapter is especially powerful, because of the importance of her work as Whitlam’s women’s adviser and because she worked closely with him. She suggests Whitlam’s consciousness of feminism grew during his term in office. By September 1974, he understood his own policies and reforms could only go so far.

Fundamental cultural shift was required, "We have to attack the social inequalities, the hidden and usually unarticulated assumptions which affect women not only in employment but in the whole range of their opportunities in life […] this requires a re-education of the community."

Reid encapsulates how she forged her own novel role: travelling around Australia to listen to women of all backgrounds, holding meetings in venues ranging from factories, farms and universities to jails. Soon, she received more letters than anyone in the government, other than Whitlam himself. After listening and gathering women’s views, she learned how to approach parliamentarians and public servants in order to make and implement policies.

Part of the power of Reid’s chapter lies in the insights she gives readers into the revolutionary nature of women’s liberation. Feminists who hit their stride in the 1970s had bold ambitions: ending patriarchal oppression, uprooting sexism as a system of male domination, taking back control of women’s bodies and sexuality, and using consciousness-raising to find alternatives to the confinement of women as housewives.

Some in women’s liberation questioned the possibility of creating revolution from within government. But Reid’s chapter showcases her remarkable ability to take the fundamental insights of the movement and use them. She listened to Australian women and applied her insights and feminist principles to the key areas of employment and financial discrimination, education, childcare, social welfare and urban planning.

A dynamic movement

One vibrant thread connecting several chapters is the dynamism of the women’s liberation movement: not least, the Canberra group where Reid developed her feminism. Biff Ward recalls the night in early 1973 that she and other Canberra women from the women’s liberation movement attended the party held for the 18 shortlisted applicants for the women’s adviser job.

It was a seemingly ordinary Saturday-night event in a suburban home: the prime minister was among the prominent Labor men present. Ward recalls the extraordinary atmosphere at the party, with the government luminaries aware of their own newfound power, yet “sidelined” by the women. These women knew each other from the movement and constituted “a tribe” that had the men on edge, because of the women’s shared confidence and agenda.

The chapter on the late Pat Eatock, the Aboriginal feminist who had travelled from Sydney to Canberra in early 1972 for the Tent Embassy, then stayed to move into the Women’s House (run by the Women’s Liberation group) is co-written by her daughter Cathy Eatock. In 1972 Pat Eatock became the first Indigenous woman to stand for federal parliament. Later she became a public servant, an academic and a pioneer in Aboriginal television. She was part of the Canberra women’s liberation movement, despite not feeling accepted by some members.

On balance, Eatock believed the movement changed her life for the better. She participated in the celebrated 1975 Women and Politics Conference, and was in the Australian delegation to the International Women’s Year Conference in Mexico City, where she found Australian feminist theory was “leading the world”.

Greater expectations

The book is organised into five sections, each introduced by a relevant expert. In the section on law, Elizabeth Evatt succinctly describes her path-breaking roles. She was deputy president of the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission (predecessor to the Fair Work Commission), chair of the Royal Commission on Human Relationships 1974-77 (which brought abortion, homosexuality and domestic violence into the spotlight); and first chief judge of the Family Court of Australia. The latter was created by the Family Law Act of 1975, which introduced no-fault divorce.

In her conclusion, Evatt laments the recent merger of the Family Court with the Federal Circuit Court, and hails the Family Law Act as one of Whitlam’s great legacies.

In the health and social policy section, former Labor Senator Margaret Reynolds recalls observing the Whitlam government’s achievements from conservative Townsville, where she was a founding member of the local Women’s Electoral Lobby. As a teacher, she saw how the reforms in education benefited regional schools and children. And the Townsville CAE introduced a training program for teaching monitors from remote communities, which particularly helped Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

In the section on legacies, author and former “femocrat” Sara Dowse catalogues the disastrous social consequences of neoliberalism, which have been braided with the many real and important gains for women since the 1970s. Hope lies, she suggests, in women’s greater expectations for their own lives.

I have focused on essays by senior feminists, but the 16 wide-ranging chapters include contributions from younger authors, too.

From our current standpoint, the fervour of the 1970s is enviable. It’s very promising that the 2022 election brought an influx of new women MPs. But if we’re going to conquer intimate violence, women’s homelessness and the gender pay gap, we need another feminist revolution.

Image credits: Getty Images

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.